Which Group Of Organisms (Ciliates, Animals, Or Plants) Has The Most Complex Cells?

| Ciliate Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

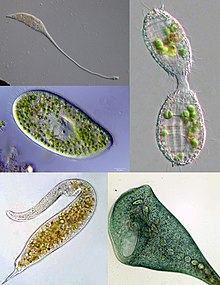

| Some examples of ciliate diversity. Clockwise from peak left: Lacrymaria, Coleps, Stentor, Dileptus, Paramecium | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| (unranked): | Diaphoretickes |

| Clade: | SAR |

| Infrakingdom: | Alveolata |

| Phylum: | Ciliophora Doflein, 1901 emend. |

| Subphyla and classes[1] | |

See text for subclasses. | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The ciliates are a group of protozoans characterized by the presence of pilus-like organelles called cilia, which are identical in structure to eukaryotic flagella, simply are in full general shorter and present in much larger numbers, with a different undulating pattern than flagella. Cilia occur in all members of the group (although the peculiar Suctoria only have them for part of their life-bicycle) and are variously used in swimming, crawling, zipper, feeding, and sensation.

Ciliates are an important grouping of protists, common most anywhere there is h2o — in lakes, ponds, oceans, rivers, and soils. Nigh iv,500 unique free-living species accept been described, and the potential number of extant species is estimated at 27,000–twoscore,000.[2] Included in this number are many ectosymbiotic and endosymbiotic species, also as some obligate and opportunistic parasites. Ciliate species range in size from as little as 10 µm in some colpodeans to as much as 4 mm in length in some geleiids, and include some of the nearly morphologically complex protozoans.[3] [4]

In most systems of taxonomy, "Ciliophora" is ranked as a phylum[5] nether any of several kingdoms, including Chromista,[6] Protista[7] or Protozoa.[8] In some older systems of classification, such as the influential taxonomic works of Alfred Kahl, ciliated protozoa are placed within the form "Ciliata"[nine] [ten] (a term which can also refer to a genus of fish). In the taxonomic scheme endorsed by the International Guild of Protistologists, which eliminates formal rank designations such as "phylum" and "course", "Ciliophora" is an unranked taxon within Alveolata.[11] [12]

Cell structure [edit]

Nuclei [edit]

Unlike nigh other eukaryotes, ciliates have ii unlike sorts of nuclei: a tiny, diploid micronucleus (the "generative nucleus," which carries the germline of the cell), and a large, ampliploid macronucleus (the "vegetative nucleus," which takes care of full general cell regulation, expressing the phenotype of the organism).[thirteen] [xiv] The latter is generated from the micronucleus by distension of the genome and heavy editing. The micronucleus passes its genetic cloth to offspring, but does not limited its genes. The macronucleus provides the small nuclear RNA for vegetative growth.[fifteen] [14]

Partitioning of the macronucleus occurs in near ciliate species, apart from those in class Karyorelictea, whose macronuclei are replaced every time the cell divides.[16] Macronuclear division is achieved by amitosis, and the segregation of the chromosomes occurs past a process whose machinery is unknown.[14] Subsequently a certain number of generations (200-350, in Paramecium aurelia, and as many as 1,500 in Tetrahymena[16] ) the cell shows signs of aging, and the macronuclei must be regenerated from the micronuclei. Commonly, this occurs post-obit conjugation, after which a new macronucleus is generated from the post-bridal micronucleus.[14]

Cytoplasm [edit]

Nutrient vacuoles are formed through phagocytosis and typically follow a particular path through the cell equally their contents are digested and broken down past lysosomes so the substances the vacuole contains are and then small enough to diffuse through the membrane of the nutrient vacuole into the jail cell. Annihilation left in the food vacuole by the time it reaches the cytoproct (anal pore) is discharged by exocytosis. Virtually ciliates also have one or more prominent contractile vacuoles, which collect h2o and expel it from the cell to maintain osmotic pressure, or in some office to maintain ionic balance. In some genera, such as Paramecium, these have a distinctive star shape, with each bespeak beingness a collecting tube.

Specialized structures in ciliates [edit]

By and large, body cilia are arranged in mono- and dikinetids, which respectively include one and two kinetosomes (basal bodies), each of which may support a cilium. These are arranged into rows called kineties, which run from the anterior to posterior of the cell. The body and oral kinetids make up the infraciliature, an organization unique to the ciliates and of import in their classification, and include diverse fibrils and microtubules involved in coordinating the cilia. In some forms there are besides trunk polykinetids, for instance, amongst the spirotrichs where they generally form beard called cirri.

The infraciliature is one of the main components of the jail cell cortex. Others are the alveoli, small vesicles under the cell membrane that are packed against it to form a pellicle maintaining the jail cell's shape, which varies from flexible and contractile to rigid. Numerous mitochondria and extrusomes are also generally present. The presence of alveoli, the construction of the cilia, the form of mitosis and diverse other details indicate a close human relationship between the ciliates, Apicomplexa, and dinoflagellates. These superficially unlike groups make up the alveolates.

Feeding [edit]

Near ciliates are heterotrophs, feeding on smaller organisms, such as bacteria and algae, and detritus swept into the oral groove (oral fissure) past modified oral cilia. This usually includes a serial of membranelles to the left of the mouth and a paroral membrane to its correct, both of which arise from polykinetids, groups of many cilia together with associated structures. The food is moved by the cilia through the mouth pore into the gullet, which forms food vacuoles.

Feeding techniques vary considerably, however. Some ciliates are mouthless and feed past assimilation (osmotrophy), while others are predatory and feed on other protozoa and in particular on other ciliates. Some ciliates parasitize animals, although simply ane species, Balantidium coli, is known to cause affliction in humans.[17]

Reproduction and sexual phenomena [edit]

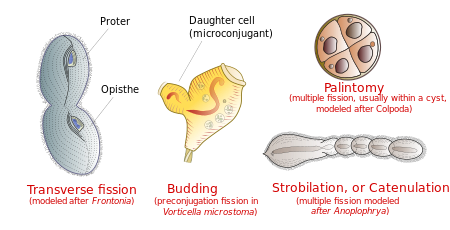

Most ciliates divide transversally, but other kinds of binary fission occur in some species

Reproduction [edit]

Ciliates reproduce asexually, by diverse kinds of fission.[sixteen] During fission, the micronucleus undergoes mitosis and the macronucleus elongates and undergoes amitosis (except amongst the Karyorelictean ciliates, whose macronuclei do not dissever). The jail cell then divides in two, and each new prison cell obtains a copy of the micronucleus and the macronucleus.

Ciliate undergoing the concluding processes of binary fission

Typically, the cell is divided transversally, with the anterior half of the ciliate (the proter) forming ane new organism, and the posterior half (the opisthe) forming another. Nonetheless, other types of fission occur in some ciliate groups. These include budding (the emergence of small ciliated offspring, or "swarmers", from the body of a mature parent); strobilation (multiple divisions forth the cell body, producing a chain of new organisms); and palintomy (multiple fissions, usually within a cyst).[18]

Fission may occur spontaneously, as function of the vegetative cell cycle. Alternatively, it may proceed equally a effect of self-fertilization (autogamy),[xix] or it may follow conjugation, a sexual miracle in which ciliates of compatible mating types commutation genetic material. While conjugation is sometimes described as a form of reproduction, information technology is not straight connected with reproductive processes, and does not direct result in an increment in the number of individual ciliates or their progeny.[20]

Conjugation [edit]

- Overview

Ciliate conjugation is a sexual miracle that results in genetic recombination and nuclear reorganization within the cell.[20] [18] During conjugation, two ciliates of a compatible mating type course a bridge between their cytoplasms. The micronuclei undergo meiosis, the macronuclei disappear, and haploid micronuclei are exchanged over the span. In some ciliates (peritrichs, chonotrichs and some suctorians), conjugating cells become permanently fused, and one conjugant is absorbed by the other.[17] [21] In near ciliate groups, however, the cells separate after conjugation, and both form new macronuclei from their micronuclei.[22] Conjugation and autogamy are always followed past fission.[xviii]

In many ciliates, such as Paramecium, conjugating partners (gamonts) are similar or indistinguishable in size and shape. This is referred to equally "isogamontic" conjugation. In some groups, partners are different in size and shape. This is referred to as "anisogamontic" conjugation. In sessile peritrichs, for instance, one sexual partner (the microconjugant) is modest and mobile, while the other (macroconjugant) is large and sessile.[twenty]

- Stages of conjugation

Stages of conjugation in Paramecium caudatum

In Paramecium caudatum, the stages of conjugation are as follows (run into diagram at correct):

- Compatible mating strains meet and partly fuse

- The micronuclei undergo meiosis, producing four haploid micronuclei per cell.

- Three of these micronuclei disintegrate. The 4th undergoes mitosis.

- The ii cells substitution a micronucleus.

- The cells and so separate.

- The micronuclei in each cell fuse, forming a diploid micronucleus.

- Mitosis occurs 3 times, giving rise to eight micronuclei.

- Four of the new micronuclei transform into macronuclei, and the old macronucleus disintegrates.

- Binary fission occurs twice, yielding four identical daughter cells.

Dna rearrangements (gene scrambling) [edit]

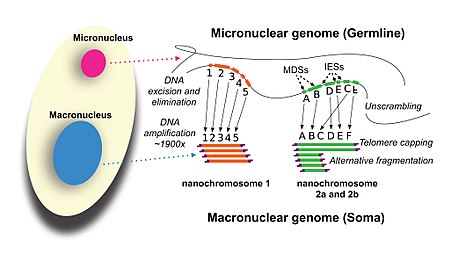

Ciliates contain two types of nuclei: somatic "macronucleus" and the germline "micronucleus". Merely the Deoxyribonucleic acid in the micronucleus is passed on during sexual reproduction (conjugation). On the other mitt, only the DNA in the macronucleus is actively expressed and results in the phenotype of the organism. Macronuclear DNA is derived from micronuclear DNA by amazingly extensive Deoxyribonucleic acid rearrangement and amplification.

Evolution of the Oxytricha macronuclear genome from micronuclear genome

The macronucleus begins as a copy of the micronucleus. The micronuclear chromosomes are fragmented into many smaller pieces and amplified to give many copies. The resulting macronuclear chromosomes often incorporate but a single gene. In Tetrahymena, the micronucleus has ten chromosomes (v per haploid genome), while the macronucleus has over 20,000 chromosomes.[23]

In addition, the micronuclear genes are interrupted past numerous "internal eliminated sequences" (IESs). During evolution of the macronucleus, IESs are deleted and the remaining cistron segments, macronuclear destined sequences (MDSs), are spliced together to give the operational cistron. Tetrahymena has about 6,000 IESs and about 15% of micronuclear DNA is eliminated during this process. The procedure is guided by small RNAs and epigenetic chromatin marks.[23]

In spirotrich ciliates (such as Oxytricha), the process is even more than complex due to "cistron scrambling": the MDSs in the micronucleus are often in different club and orientation from that in the macronuclear gene, and so in improver to deletion, DNA inversion and translocation are required for "unscrambling". This process is guided by long RNAs derived from the parental macronucleus. More than than 95% of micronuclear DNA is eliminated during spirotrich macronuclear development.[23]

Fossil record [edit]

Until recently, the oldest ciliate fossils known were tintinnids from the Ordovician period. In 2007, Li et al. published a clarification of fossil ciliates from the Doushantuo Formation, about 580 million years ago, in the Ediacaran period. These included ii types of tintinnids and a possible ancestral suctorian.[24] A fossil Vorticella has been discovered within a leech cocoon from the Triassic period, virtually 200 million years ago.[25]

Classification [edit]

Several dissimilar nomenclature schemes have been proposed for the ciliates. The following scheme is based on a molecular phylogenetic analysis of upward to four genes from 152 species representing 110 families:[1]

Subphylum Postciliodesmatophora [edit]

- Grade Heterotrichea (e.yard. Stentor)

- Course Karyorelictea

Subphylum Intramacronucleata [edit]

- Class Armophorea

- Class Cariacotrichea (only one species, Cariacothrix caudata)

- Class Muranotrichea

- Class Parablepharismea

- Class Colpodea (due east.g. Colpoda)

- Class Litostomatea

- Subclass Haptoria (east.grand. Didinium)

- Subclass Rhynchostomatia

- Subclass Trichostomatia (eastward.grand. Balantidium)

- Class Nassophorea

- Grade Phyllopharyngea

- Subclass Chonotrichia

- Bracket Cyrtophoria

- Subclass Rhynchodia

- Subclass Suctoria (due east.m. Podophyra)

- Bracket Synhymenia

- Class Oligohymenophorea

- Bracket Apostomatia

- Subclass Astomatia

- Bracket Hymenostomatia (e.1000. Tetrahymena)

- Bracket Peniculia (e.g. Paramecium)

- Subclass Peritrichia (e.g. Vorticella)

- Bracket Scuticociliatia

- Class Plagiopylea

- Class Prostomatea (e.k. Coleps)

- Form Protocruziea

- Course Spirotrichea

- Subclass Choreotrichia

- Subclass Euplotia

- Bracket Hypotrichia

- Subclass Licnophoria

- Subclass Oligotrichia

- Subclass Phacodiniidea

- Subclass Protohypotrichia

Other [edit]

Some old classifications included Opalinidae in the ciliates. The fundamental departure between multiciliate flagellates (e.g., hemimastigids, Stephanopogon, Multicilia, opalines) and ciliates is the presence of macronuclei in ciliates lone.[26]

Pathogenicity [edit]

The only member of the ciliate phylum known to be pathogenic to humans is Balantidium coli,[27] [28] which causes the affliction balantidiasis. It is not pathogenic to the domestic squealer, the primary reservoir of this pathogen.[29]

References [edit]

- ^ a b Gao, Feng; Warren, Alan; Zhang, Qianqian; Gong, Jun; Miao, Miao; Lord's day, Ping; Xu, Dapeng; Huang, Jie; Yi, Zhenzhen (2016-04-29). "The All-Data-Based Evolutionary Hypothesis of Ciliated Protists with a Revised Classification of the Phylum Ciliophora (Eukaryota, Alveolata)". Scientific Reports. six: 24874. Bibcode:2016NatSR...624874G. doi:x.1038/srep24874. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC4850378. PMID 27126745.

- ^ Foissner, W.; Hawksworth, David, eds. (2009). Protist Diversity and Geographical Distribution. Topics in Biodiversity and Conservation. Vol. eight. Springer Netherlands. p. 111. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2801-3. ISBN9789048128006.

- ^ Nielsen, Torkel Gissel; Kiørboe, Thomas (1994). "Regulation of zooplankton biomass and product in a temperate, littoral ecosystem. ii. Ciliates". Limnology and Oceanography. 39 (3): 508–519. Bibcode:1994LimOc..39..508N. doi:10.4319/lo.1994.39.iii.0508.

- ^ Lynn, Denis (2008). The Ciliated Protozoa third Edition . Springer. pp. 129. ISBN978-one-4020-8238-2.

- ^ "ITIS Report". Integrated Taxonomic Information System . Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (2018-01-01). "Kingdom Chromista and its 8 phyla: a new synthesis emphasising periplastid poly peptide targeting, cytoskeletal and periplastid development, and aboriginal divergences". Protoplasma. 255 (1): 297–357. doi:10.1007/s00709-017-1147-3. ISSN 1615-6102. PMC5756292. PMID 28875267.

- ^ Yi Z, Song Due west, Clamp JC, Chen Z, Gao Southward, Zhang Q (Dec 2008). "Reconsideration of systematic relationships inside the order Euplotida (Protista, Ciliophora) using new sequences of the cistron coding for small-scale-subunit rRNA and testing the utilize of combined data sets to construct phylogenies of the Diophrys-complex". Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. l (3): 599–607. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2008.12.006. PMID 19121402.

- ^ Miao G, Song W, Chen Z, et al. (2007). "A unique euplotid ciliate, Gastrocirrhus (Protozoa, Ciliophora): cess of its phylogenetic position inferred from the small-scale subunit rRNA gene sequence". J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 54 (4): 371–8. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2007.00271.x. PMID 17669163. S2CID 25977768.

- ^ Alfred Kahl (1930). Urtiere oder Protozoa I: Wimpertiere oder Ciliata -- Volume I General Section And Prostomata.

- ^ "Medical Definition of CILIATA". world wide web.merriam-webster.com . Retrieved 2017-12-22 .

- ^ Adl, Sina M.; Bass, David; Lane, Christopher East.; Lukeš, Julius; Schoch, Conrad L.; Smirnov, Alexey; Agatha, Sabine; Berney, Cedric; Brown, Matthew W.; Burki, Fabien; Cárdenas, Paco (2019). "Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Multifariousness of Eukaryotes". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 66 (1): 4–119. doi:10.1111/jeu.12691. ISSN 1550-7408. PMC6492006. PMID 30257078.

- ^ Adl, Sina Thousand.; et al. (2005). "The new higher level classification of eukaryotes with emphasis on the taxonomy of protists". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 52 (five): 399–451. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00053.x. PMID 16248873.

- ^ Raikov, I.B. (1969). "The Macronucleus of Ciliates". Research in Protozoology. 3: four–115. ISBN9781483186146.

- ^ a b c d Archibald, John M.; Simpson, Alastair Thousand. B.; Slamovits, Claudio H., eds. (2017). Handbook of the Protists (2 ed.). Springer International Publishing. p. 691. ISBN978-3-319-28147-6.

- ^ Prescott, D G (June 1994). "The DNA of ciliated protozoa". Microbiological Reviews. 58 (2): 233–267. doi:x.1128/mr.58.2.233-267.1994. ISSN 0146-0749. PMC372963. PMID 8078435.

- ^ a b c H., Lynn, Denis (2008). The ciliated protozoa : characterization, classification, and guide to the literature. New York: Springer. p. 324. ISBN9781402082382. OCLC 272311632.

- ^ a b Lynn, Denis (2008). The Ciliated Protozoa: Characterization, Classification, and Guide to the Literature (three ed.). Springer. pp. 58. ISBN978-one-4020-8238-ii.

1007/978-i-4020-8239-9

- ^ a b c H., Lynn, Denis (2008). The ciliated protozoa : characterization, nomenclature, and guide to the literature. New York: Springer. p. 23. ISBN9781402082382. OCLC 272311632.

- ^ Berger JD (Oct 1986). "Autogamy in Paramecium. Prison cell cycle stage-specific delivery to meiosis". Exp. Prison cell Res. 166 (2): 475–85. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(86)90492-1. PMID 3743667.

- ^ a b c Raikov, I.B (1972). "Nuclear phenomena during conjugation and autogamy in ciliates". Research in Protozoology. 4: 149.

- ^ Finley, Harold E. "The conjugation of Vorticella microstoma." Transactions of the American Microscopical Society (1943): 97-121.

- ^ "Introduction to the Ciliata". Retrieved 2009-01-xvi .

- ^ a b c Mochizuki, Kazufumi (2010). "DNA rearrangements directed by non-coding RNAs in ciliates". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: RNA. i (3): 376–387. doi:10.1002/wrna.34. PMC3746294. PMID 21956937.

- ^ Li, C.-W.; et al. (2007). "Ciliated protozoans from the Precambrian Doushantuo Formation, Wengan, South China". Geological Guild, London, Special Publications. 286 (i): 151–156. Bibcode:2007GSLSP.286..151L. doi:ten.1144/SP286.11. S2CID 129584945.

- ^ Bomfleur, Benjamin; Kerp, Hans; Taylor, Thomas N.; Moestrup, Øjvind; Taylor, Edith L. (2012-12-eighteen). "Triassic leech cocoon from Antarctica contains fossil bell animal". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United states of America. 109 (51): 20971–20974. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10920971B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1218879109. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC3529092. PMID 23213234.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith, T. (2000). Flagellate megaevolution: the ground for eukaryote diversification. In: Leadbeater, B.Due south.C., Green, J.C. (eds.). The Flagellates. Unity, diverseness and evolution. London: Taylor and Francis, pp. 361-390, p. 362, [i].

- ^ "Balantidiasis". DPDx — Laboratory Identification of Parasitic Diseases of Public Health Business organization. Centers for Affliction Command and Prevention. 2013.

- ^ Ramachandran, Ambili (23 May 2003). "Introduction". The Parasite: Balantidium coli The Affliction: Balantidiasis. ParaSite. Stanford University.

- ^ Schister, Frederick L. and Lynn Ramirez-Avila (Oct 2008). "Current Earth Status of Balantidium coli". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 21 (iv): 626–638. doi:10.1128/CMR.00021-08. PMC2570149. PMID 18854484.

Further reading [edit]

- Lynn, Denis H. (2008). The ciliated protozoa : characterization, nomenclature, and guide to the literature. New York: Springer. ISBN9781402082382. OCLC 272311632.

- Ciliates : cells as organisms. Hausmann, Klaus., Bradbury, Phyllis C. (Phyllis Clarke). Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer Verlag. 1996. ISBN978-3437250361. OCLC 34782787.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - An illustrated guide to the protozoa : organisms traditionally referred to as protozoa, or newly discovered groups. Lee, John J., Leedale, Gordon F., Bradbury, Phyllis C. (Phyllis Clarke) (2nd ed.). Lawrence, Kan., The statesA.: Society of Protozoologists. 2000. ISBN9781891276224. OCLC 49191284.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

External links [edit]

-

Media related to Ciliophora at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ciliophora at Wikimedia Commons

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ciliate

Posted by: mcelroywitaysen.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Which Group Of Organisms (Ciliates, Animals, Or Plants) Has The Most Complex Cells?"

Post a Comment